Pop Quiz

1. Why is a double-blind, placebo-controlled study with random assignment to conditions the gold standard for testing the effectiveness of a treatment?

2. If participants are not blind to their condition and know the nature of their treatment, what problems does that lack of control introduce?

3. Would you use a drug if the only study showing that it was effective used a design in which those people who were given the drug knew that they were taking the treatment and those who were not given the drug knew they were not receiving the treatment? If not, why not?

Most people who have taken a research methods class (or introductory psychology) will be able to answer all three. The gold standard controls for participant and experimenter expectations and helps to control for unwanted variation between the people in each group. If participants know their treatment, then their beliefs and expectations might affect the outcome. I would hope that you wouldn't trust a drug tested without a double-blind design. Without such a design, any improvement by the treatment group need not have resulted from the drug.

In a paper out today in Perspectives on Psychological Science, my colleagues (Walter Boot, Cary Stothart, and Cassie Stutts) and I note that psychology

If participants know the treatment they are receiving, they may form expectations about how that treatment will affect their performance on the outcome measures. And, participants in the control condition might form different expectations. If so, any difference between the two groups might result from the consequences of those expectations (e.g., arousal, motivation, demand characteristics, etc.) rather than from the treatment itself.A truly double blind design addresses that problem—if people don't know whether they are receiving the treatment or the placebo, their expectations won't differ. Without a double blind design, researchers have an obligation to use other means to control for differential expectations. If they don't, then a bigger improvement in the treatment group tells you nothing conclusive about the effectiveness of the treatment. Any improvement could be due to the treatment, to different expectations, or to some combination of the two. No causal claims about the effectiveness of the treatment are justified.

If we wouldn't trust the effectiveness of a new drug when the only study testing it lacked a control for placebo effects, why should we believe a psychology intervention if it lacked any controls for differential expectations? Yet, almost all published psychology interventions attribute causal potency to interventions that lack such controls. Authors seem to ignore this known problem, reviewers don't block publication of such papers, and editors don't reject them.

Most psychology interventions have deeper problems than just a lack of controls for differential expectations. Many do not include a control group that is matched to the treatment group on everything other than the hypothesized critical ingredient of the treatment. Without such matching, any difference between the tasks could contribute to the difference performance. Some psychology interventions use completely different control tasks (e.g., crosswords puzzles as a control for working memory training, educational DVDs a control for auditory memory training, etc). Even worse, some do not even use an active control group, instead comparing performance to a "no-contact" control group that just takes a pre-test and a post-test. Worst of all, some studies use a wait-list control group that doesn't even complete the outcome measures before and after the intervention.

In my view, a psychology intervention that uses a waitlist or no-contact control should not be published. Period. Reviewers and editors should reject it without further consideration -- it tells us almost nothing about whether the treatment had any effect, and is just a pilot study (and a weak one at that).

Studies with active control groups that are not matched to the treatment intervention should be viewed as suspect—we have no idea what differences between the treatment and control condition were necessary. Even closely matched control groups do not permit causal claims if the study did nothing to check for differential expectations.

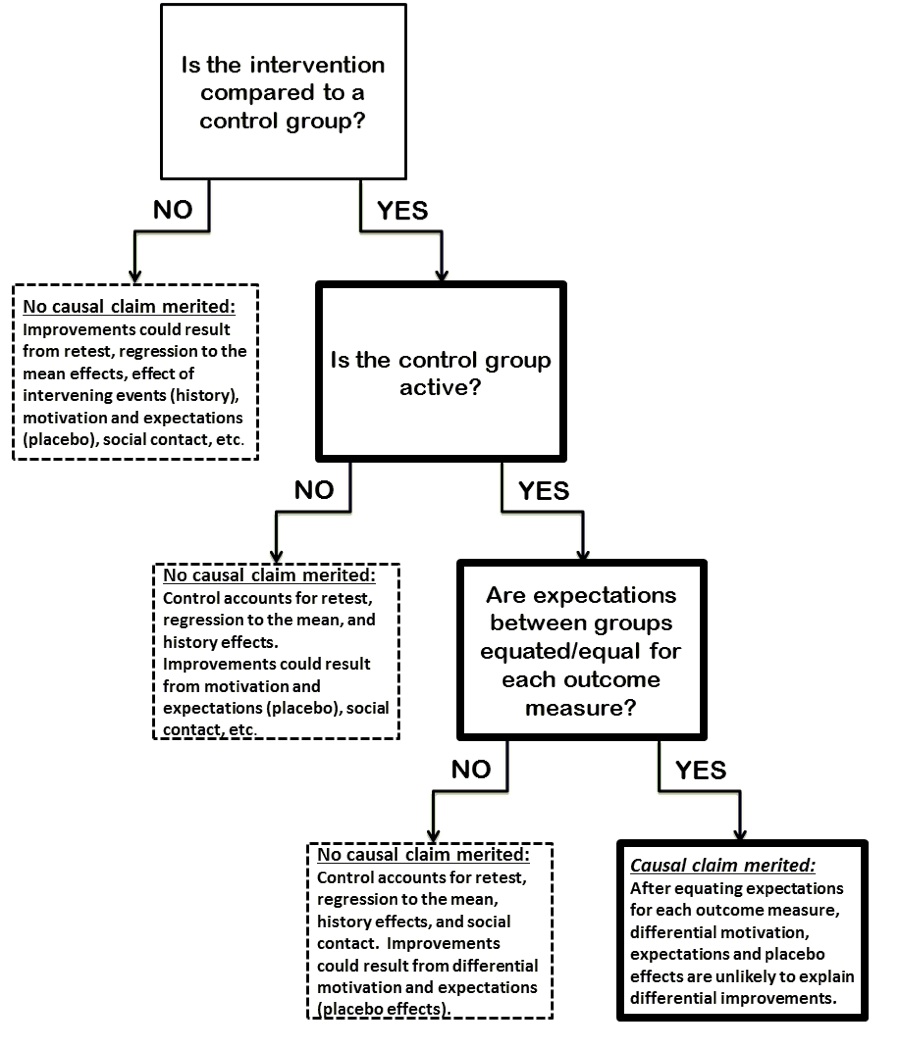

To make it easy to understand these shortcomings, here is a flow chart from our paper that illustrates when causal conclusions are merited and what we can learn from studies with weaker control conditions (short answer -- not much):

Almost no psychology interventions even fall into that lower-right box, but almost all of them make causal claims anyway. That needs to stop.

If you want to read more, check out our OpenScienceFramework Page for this paper/project. It includes an answers to a set of Frequent Questions.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.